Linux Forensics In Depth

OverView

Linux is a big target as almost every server is running some sort of Linux, In this blog post I will try to cover details as possible but also I will expect the reader to have some knowledge of using Linux, I will start with simple topics and move towards advanced ones.

Some of the content in this post is copied from the references as they described it in the best way.

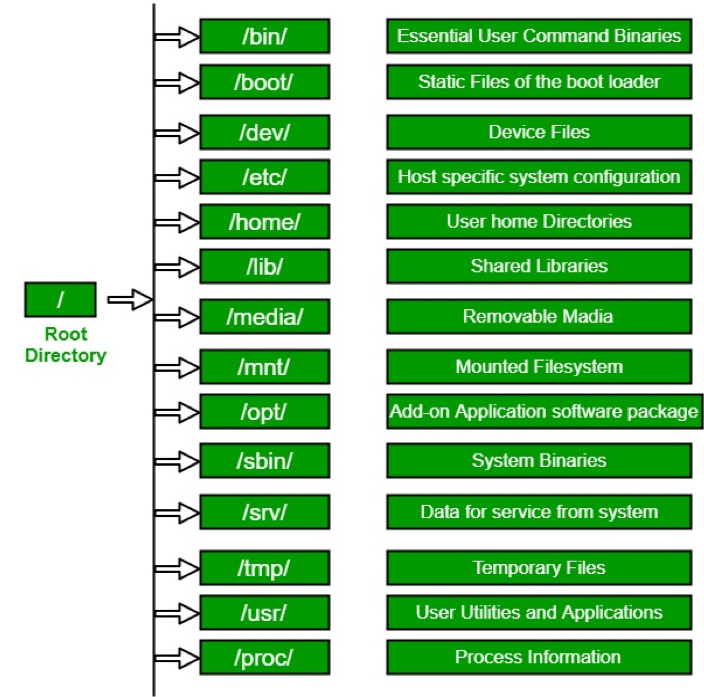

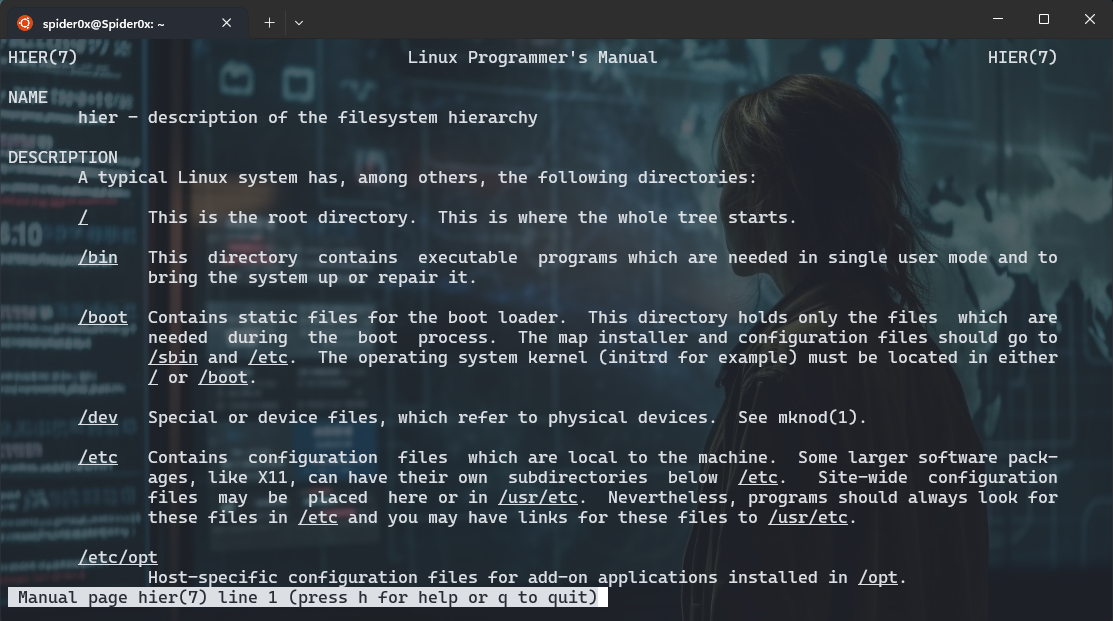

Linux Directory Layout

I can’t speak about linux forensics with out mentioning the directory layout for it, So if you are comfortable with it pass this section.

There is no stander specification forced to follow for every folder and what should be stored there so every distripution document it’s file structure in hier man page, but always top directories remain the same.

/boot/ and efi

These directories contains files related to boot process configurations like kernel parameters and previous linux kernels and initial ramfs, more details comes later.

/etc/

System wide configurations are stored here and most of them are stored in plaintext format, looking at modification and creation timestamp here is good in any forensics investigation, more details comes later.

/srv/

this folder contains servers data like FTP, HTTP…

/tmp/

This folder stores temporary data and based on the distripution configuration it may be deleted periodically or on boot.

/run/ On a running system, this directory contains runtime information like PID and lock files, systemd runtime configuration, and more. In a forensic image it will likly be empty.

/home/ and /root/

This is home folder for any user in the system and the root user folder also.

/bin/, /sbin/, /usr/bin/, and /usr/sbin/

These are the folders storing executables in the system, In general half of them is just a symlink for the other “/bin/ -> /usr/bin” and “/sbin/ -> /usr/sbin/”

/lib/ and /usr/lib/

these directory contains libraries needed by applications to run.

/usr/

The /usr/ directory contains the bulk of the system’s static read-only data. This includes binaries, libraries, documentation, and more.

/var/

The /var/ directory contains system data that is changing (variable) and usually persistent across reboots. The subdirectories below /var/ are especially interesting from a forensics perspective because they contain logs, cache, historical data, persistent temporary files, the mail and printing subsystems, and much more.

/dev/, /sys/, and /proc/

These directories provide representations of devices or kernel data structures but the contents don’t actually exist on a normal filesystem. When examining a forensic image, these directories will likely be empty.

/media/

The /media/ directory is intended to hold dynamically created mount points for mounting external removable storage, such as CDROMs or USB drives. When examining a forensic image, this directory will likely be empty. References to /media/ in logs, filesystem metadata, or other persistent data may provide information about user attached (mounted) external storage devices.

/opt/

The /opt/ directory contains add-on packages, which typically are grouped by vendor name or package name. These packages may create a self-contained directory tree to organize their own files (for example, bin/, etc/, and other common subdirectories).

/lost+found/

A /lost+found/ directory may exist on the root of every filesystem. If a filesystem repair is run (using the fsck command) and a file is found without a parent directory, that file (sometimes called an orphan) is placed in the /lost+found/ directory where it can be recovered. Such files don’t have their original names because the directory that contained the filename is unknown or missing.

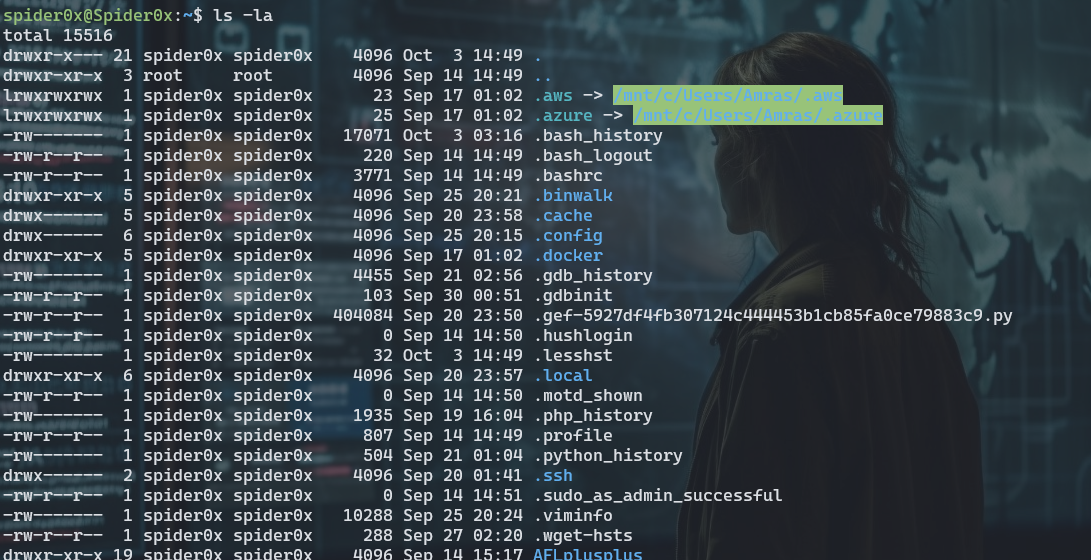

the “.” files

Applications saves It’s cashed and history and whatever the developer decided to store in hidden files or directories in the system, these hidden contents start with “.”, there is no specifications for forcing the developer to store it in a specific place.

Here is some examples on my own system.

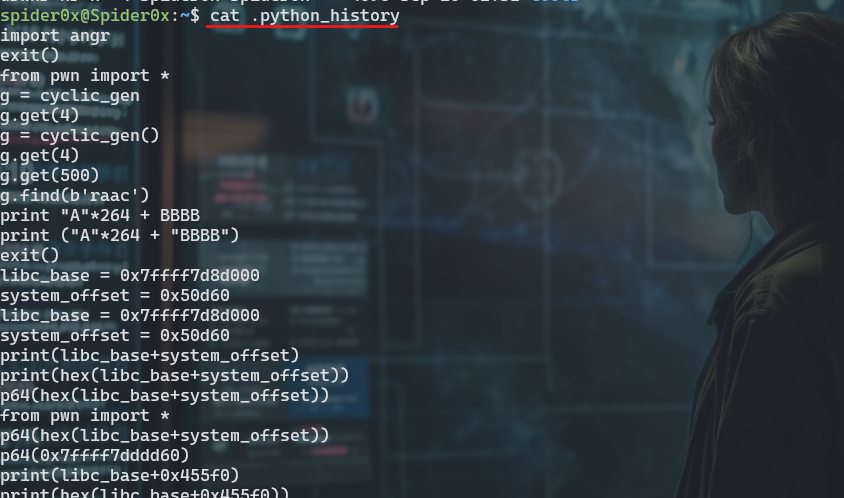

here we can see history of “bash, python, php, gdb, vim, less, wget” and there is others also. Looking at one of them like “python_history” we can see alist of all the executed commands in python shell.

as you can see you can find that I was doing some binary exploitation work and that is right you managed to get evidence of user activity, and you can construct more by looking in these files, but that is confidential for me but you got the point.

another intersting hidden folder is “.ssh” folder where you can look for hashed names on “known_hosts”, you can’t unhash them but you can find the deviations by hashing the known ones and comparing.

although there is no standerd place to store this kind of files, there is a specification for best practice recommended,The specification defines environment variables and default locations that operating systems and applications may use instead of creating their own proprietary files and directories in the user’s home directory. These location environment variables and associated default locations are:

- Data files: $XDG_DATA_HOME or default ~/.local/share/*

- Configuration files: $XDG_CONFIG_HOME or default ~/.config/*

- Non-essential cache data: $XDG_CACHE_HOME or default ~/.cache

- Runtime files: $XDG_RUNTIME_DIR or typically /run/user/UID (where UID is the numeric ID of the user)

These Data, Configuration and Cache ddirectories will contain amount of usful information for forensics investigation.

one small example of data that can be found there is in “~/.local/share/” is *.xbel file which contains recently used files, Trash which is like a recycle bin, alot of evidence resides there so make sure to take time reviewing it, I will not mention every one of them as they are self explanatory when you look at theire names or content like configurations and logs for non standerd applications.

Crashes & Dumps

Crash Dumps can provide a significant amount of evidence in forensics investigation as it saves the content of the memory in the time of a crash that can give us alot of information if a process was under attack or some one was trying to exploit it, we can get a list of crashes and theire time stamp using the followig command.

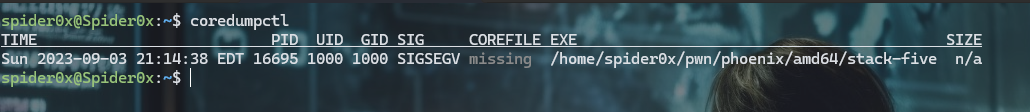

coredumpctl

As you can see here I was trying to exploit a a stack overflow in a binary in the machine and that gets recorded, although some times like in the picture the Dump it self maybe missing.

where logs and crash files is saved is different from distripution to another so You need to conduct a small searh of where this files resides in your distripution.

Linux Logs

/var/log/ is not the only place where logs are stored but definetly it’s the most important one, the logs file stored there varies between different distriputions but here some geberal ones.

-

auth.log or /var/log/secure: Logs related to authentication and security, including login attempts, authentication failures, and security-related events.

-

syslog or /var/log/messages: General system logs that capture a wide range of system events, including kernel messages and system daemon messages.

-

kern.log: Kernel-specific logs that contain messages related to the Linux kernel.

-

dmesg: Kernel boot messages and hardware-related messages.

-

boot.log: Logs related to the system boot process.

-

cron: Logs for the cron scheduling daemon, which records scheduled job executions.

-

mail.log or /var/log/maillog: Logs for mail-related services, such as Sendmail or Postfix.

-

httpd/ or /var/log/apache2/: Logs for the Apache web server.

-

nginx/: Logs for the Nginx web server.

-

mysql/ or /var/log/mariadb/: Logs for the MySQL or MariaDB database server.

-

audit/: Audit logs that record security events and access control-related information.

-

auth.log: SSH login logs.

-

wtmp and btmp: Logs that track login and logout events. wtmp records successful logins, while btmp records failed login attempts.

-

lastlog: Records the last login information for each user.

-

ufw.log: Logs for the Uncomplicated Firewall (UFW) on Ubuntu systems.

-

secure: Additional security-related logs, often found on CentOS and Red Hat-based systems.

-

auth.log: Authentication logs on Debian and Ubuntu systems.

-

alternatives.log: Logs related to the alternatives system, which manages symbolic links for system commands and libraries.

Logs in Linux have the following severities.

- 0 emergency (emerg or panic): system is unusable

- 1 alert (alert): action must be taken immediately

- 2 critical (crit): critical conditions

- 3 error (err): error conditions

- 4 warning (warn): warning conditions

- 5 notice (notice): normal but significant condition

- 6 informational (info): informational messages

- 7 debug (debug): debug-level messages

you can find rsyslog configuration in

- /etc/rsyslog.conf

- /etc/rsyslog.d/*.conf

where you can see in the first one where the logs are stored localy the “@” means stored in another place over network.

- Programs can generate messages with any facility and severity they want.

- Syslog messages sent over a network are stateless, unencrypted, and based on UDP, which means they can be spoofed or modified in transit.

- Syslog does not detect or manage dropped packets. If too many messages are sent or the network is unstable, some messages maygo missing, and logs can be incomplete.

- Text-based logfiles can be maliciously manipulated or deleted.

These are all problems with the legacy syslog way, so another entire log system is built to overcome this proclems which is Systemd Journal.

the Journal system is well documented in man page systemd-journald.

you can view a .journal file content using “journalctl –file filename” (Customized search and regular expression stuff can be done to enhance your search)

There is also non stander logs that applications and servers can create its own log files to store it’s logs, these also can provide a huge amount of foresically important data that depends on the nature of the case.

A note to add here at the end that you can add custome log role to log on your system using auditd service.

To add a custom rule to log specific events in Ubuntu’s logging system, you can use the Audit framework (Auditd). Auditd allows you to define rules that specify which system events you want to monitor and log. Here’s a general process for adding a rule:

- Edit Audit Rules Configuration:

Open the audit rules configuration file for editing using a text editor like “nano” or “vim.” This file is typically located at “/etc/audit/rules.d/audit.rules”:

sudo nano /etc/audit/rules.d/audit.rules

If the file doesn’t exist, you can create it.

- Add a Custom Rule:

In the audit rules file, you can define custom audit rules to specify what events to log. The rules follow a specific format. For example, to log all file reads in the “/etc/” directory, you can add the following rule:

-a always,exit -F dir=/etc/ -F perm=r -k etc_read

-a always,exit: This part of the rule specifies that the event should be logged when it exits (e.g., when a process finishes reading a file). -F dir=/etc/: This part specifies the directory to monitor (“/etc/”). -F perm=r: This part specifies the permission (“r” for read) to monitor. -k etc_read: This part specifies a unique key for the rule. You can customize the rule according to your needs, specifying the events, directories, permissions, and keys that match your requirements.

- Save and Close the File:

Save your changes in the editor and exit.

- Reload Audit Rules:

After adding or modifying audit rules, you need to reload the audit configuration to apply the changes:

sudo service auditd reload

This will activate the new audit rule.

- View Audit Logs:

The audit logs are typically stored in /var/log/audit/audit.log. You can view the logs using a tool like aureport or ausearch, or simply by examining the log file itself. For example, to view all events related to the “etc_read” key defined in the example rule:

ausearch -k etc_read

This command will display all events matching the specified key.

Remember that monitoring too many events or setting overly broad rules can generate a large volume of logs. Be specific with your rules to capture the events that are relevant to your monitoring needs while avoiding excessive noise. Additionally, regularly review and manage your audit logs to ensure they do not consume excessive disk space.

Software Installation

The initial state of the distripution after installation can be found in /var/log/installer here you can see different logs about installed drivers and packeges and alot of others.

Let’s start discussing *.deb files which are package installers this is actually a compressed file containing three components

debian-binaryA file containing the package format version stringcontrolA compressed archive with scripts/metadata about the packagedataA compressed archive containing the files to be installed

From a forensics perspective, we can ask many questions related to package management, such as the following:

- What packages are currently installed, and which versions?

- Who installed them, when, and how?

- Which packages were upgraded and when?

- Which packages were removed and when?

- Which repositories were used?

- Can we confirm the integrity of the packages?

- What logs, databases, and cached data can be analyzed?

- Given a particular file on the filesystem, to which package does it

- belong?

- What other timestamps are relevant?

We will focus on one package manager apt but the concept remains the same for all of them.

we can get a list of installed packages in /var/lib/dpkg/status file

here are some files to look for artifacts in:

- /var/log/dpkg.log dpkg activity, including changes to package status (install, remove, upgrade, and so on)

- /var/log/apt/history.log Start/end times of apt commands and which user ran them

- /var/log/apt/term.log Start/end times of apt command output (stdout) /var/log/apt/eipp.log.* Logs the current state of the External Installation Planner Protocol (EIPP), a system that manages dependency ordering

- /var/log/aptitude Aptitude actions that were run

- /var/log/unattended-upgrades/* Logs from automated/unattended upgrades

- /etc/dpkg/ Configuration information for dpkg is stored here

- /etc/apt/ Configuration information for apt and the sources.list and sources.list.d/* files. These files are interesting because they define the configured external repositories for a particular release is stored here

- /var/lib/dpkg/info/ directory contains several files for each installed package (this is the metadata from the DEB files). This information includes the file list (*.list), cryptographic hashes (*.md5sums), preinstall/postinstall and remove scripts, and more.

- /var/cache/apt/archives/ directory contains *.deb files that have been downloaded in the past.

-

/var/cache/debconf/ directory is a central location for package configuration information and templates.

- /var/lib/snapd/snaps/ Contains downloaded snaps

- ~/.local/lib/python/ site-packages and ~/usr/lib/python/ site-packages are where pip installed packeges saved.

Login & User Interaction Forensics

- /var/log/wtmp History of successful logins and logouts(can be parsed using “last -f filename”)

- /var/log/btmp History of failed login attempts(can be parsed using “lastb -f filename”)

- /var/log/lastlog Most recent user logins

- /var/run/utmp Current users logged in (only on running systems)

An Interesting place to look at a forensics investigation is initialization scripts

- /etc/profile

- /etc/profile.d/*

- ~/.bash_profile

- /etc/bash.bashrc

- ~/.bashrc

the profile file runs once at the first shell and “*rc” files runs every time you open a shell.

- /etc/bash.bash_logout

- ~/.bash_logout

these files also run one on exit and logout.

Environment variables are also a good place to look where you can find more about the user’s default editor which may tell you where to look for more evidence and customized environment variables which can give you good hints.

here are some places to look at defult environment variables at login.

- /etc/security/pam_env.conf

- /etc/environment

- /etc/environment.d/*.conf

- /usr/lib/environment.d/*.conf

- ~/.config/environment.d/*.conf

you can look at “HIST*” environment variables where the shell history is configured that will tell you about where the shell history stored and how it’s configured.

Another note here is that command history of a shell is written only after the shell exits.

Also, note that the newly written bash history dropped to the disk is written to a new inode and the old one is still there in the disk unallocated so you can find old bash history files using carving.

Windows manegers also have some startup “*.desktop” files have the applications to start at startup.

- /etc/xdg/autostart/*

- ~/.config/autostart/*

For the Desktop setting, there is a database called dconf which is much like the Windows registry where the data is stored in hierarchy key-value pairs, I will give a look to “GNOME” desktop manager.

here you can find a tool to parse this database content.

the “dconf” files can be found in “~/.config/dconf/” and “/etc/dconf/db/” as example you can look at “user” database where user setting can be found.

There is alot of Clipboard manegers out there that stores from 5-20 history copied data but as there is alot out there you will need to search for where your maneger stores this data.

Recent Documents and favourites in linux are kept track of for every user in linux in different places like…

- .local/share/recently-used.xbel

- .local/user-places.xbel

- .local/share/Recent Documents/

Search history also is kept track of for every user each desktop manger has it’s own way, for example in GNOME search is saved to “~/.cache/tracker3/files” as sqlite databases.

Cheat sheet

here are some good places to look for persistence

- /etc/cron*/

- /etc/incron.d/*

- /etc/init.d/*

- /etc/rc.d/

- /etc/systemd/system/*

- /etc/update.d/*

- /var/spool/cron/*

- /var/spool/incron/*

-

/var/run/motd.d/*

- /etc/passwd

- /etc/sudoers

- ~/.ssh/authorized_keys

- ~/.bashrc

You can get a list of places where you can find forensic evidence in this cheat sheet

Resources

https://nostarch.com/practical-linux-forensics is my primery resource.